D. K. Banerjee

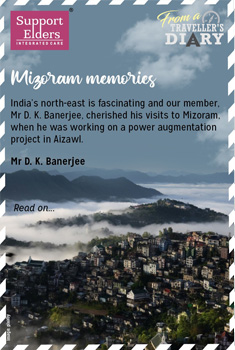

India’s north-east is fascinating and our member, Mr D. K. Banerjee, cherished his visits to Mizoram, when he was working on a power augmentation project in Aizawl.

It was in 1974-75; I was working with Escorts Ltd in Kolkata, when a tall, handsome middle-aged gentleman, whom I had not met earlier, walked into my office and introduced himself as P. P. John, a businessman from Aizawl, Mizoram. Mr John, a Kerala Christian, had married a Mizo lady and settled in Aizawl, where he ran his business. It was business that brought him to my office.

Power shortage was rampant in India in those and Mizoram was not spared. Mr John told us of the proposals to increase Aizawl’s generation capacity and how he could help us to participate in the programme. Should we succeed in our bid, he would help us locally to execute the project. It seemed a good idea and the Escorts management decided that my colleague, Mr H. P. Singh from Bombay and I would visit Aizawl. Silchar’s Kumbhirgram airport was the nearest to Aizawl and Indian Airlines operated a Fokker Friendship direct flight from Kolkata.

It was a two-hour flight because one could not overfly East Pakistan in those days. Flights to India’s north-east were generally operated from early mornings and returned by the afternoon because the sector often faced turbulent weather. Evening flights were started only after Boeing 737 aircrafts were put into service. We left Dumdum at around 6 am and reached Silchar around 8 am with a very good breakfast served enroute. The aircraft ran into one bad weather once, when things got a bit uncomfortable because the aircraft was small and flew at a low altitude.

The captain advised passengers to fasten seat belts but a middle-aged lady, sitting one row ahead of me in the opposite bay, paid no heed and was promptly thrown up and landed in the aisle. The air hostesses could not help her because of the turbulence and the lady stayed on the floor. It was a lesson for me and I keep my seat belt fastened as far as possible.

Mr John’s younger brother, who looked after the Silchar office, met us at the airport but we were disappointed that we could not proceed to Aizawl because we needed an inner line pass for travel that would take half a day. So we stayed at a nice hotel, Ellora, with some open space and garden, where the food was excellent.

We left for Aizawl the next morning with our passes in an Ambassador, for a 173-km journey. There were no SUVs or Tata Sumos then; only Ambassadors, Fiats and jeeps. The helpful John junior accompanied us on a picturesque journey with distant hills on the horizon as we drove through the plains. Our inner line permits were checked at Vairengte and we proceeded to Kolasib, travelling through little towns and stopped for tea.

The tea shop was run by a Mizo lady who served hot and refreshing tea with lots of sugar and milk along with some locally-baked biscuits. Shops in Mizoram are run by the ladies while the men work the fields. The tea was similar elsewhere in Mizoram, in the various offices that I visited, including government offices, where the people were courteous and helpful.

The road was far from good though. The 173 km took us nine hours to cover and the terrain got hilly, with roads badly broken in places, some stretches without a tar cover. Landslides and rains constantly damaged the roads that the Border Roads Organisation tried to maintain. I later learnt from my uncle, P. K. Mukerjee (former Director, Postal Services, 1954), who was based at Silchar as a postal inspector in his youth, that it took two and half days by bus and foot for him to reach Aizawl. The car was getting heated and had to be cooled with water and we kept our fingers crossed because we wanted to reach Aizawl before dusk.

The tiring journey was made interesting by the fascinating landscape with paddy grown in steps on the mountains in several places. I learnt about the local jhum cultivation. Finally, bigger houses and shops sailed into view and we knew Aizawl was nigh so was the wonderful hospitality of Mr John, who put us up in the extension wing of his house. He thought that we would be more comfortable and safe at his house.

It was a lovely family with four school-going children. Ms John was a caring mother and a very kind hostess. What impressed me most was that she was also acquainted with the family business and actively participated in it. In my subsequent visits, I have stayed in government circuit houses and at Assam Rifles transit guest houses. The hospitality of the Johns’ home is, however, etched in my memory. Mr John is no more but he survives through his contributions for spreading education and through the Government Johnson College at Aizawl, which is named after him.